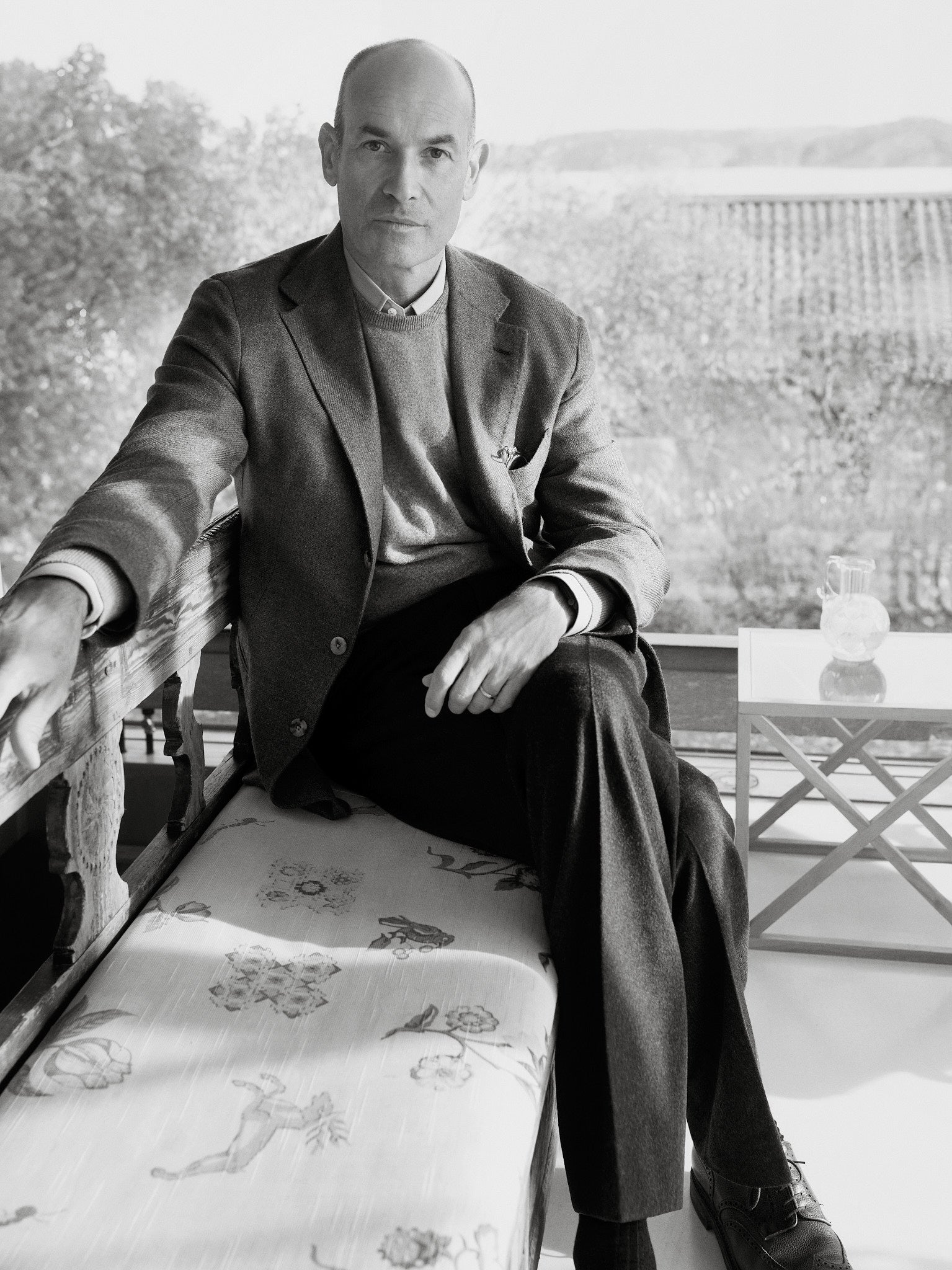

They say that the capacity to keep several – sometimes conflicting – thoughts in your mind alive at the same time is a true sign of intelligence. Rationality and spirituality or for that matter art and commerce are for most people perceived as incompatible dichotomies and cultivating both simultaneously is far from easy. However, being open to otherness and persisting in entertaining the idea that your preconceived ideas could in fact be all wrong takes courage rather than intelligence. Few people I know inhabit more of this courage than Swedish industrialist and philanthropist Daniel Sachs.

Behind Daniel’s desk in his office in Stockholm sits a card that reads “Industry without art is brutality!” and while Daniel’s commitment to the arts in Sweden has been vast, it is perhaps for his work for democracy and inclusion he is more prolific internationally. Beyond his work in business, he has been anointed Young Global Leader by World Economic Forum, he has been Chairman of the Swedish National Theatre as well as a founding member of the European Council on Foreign Relations. Through his own foundation, he is a co-founder of the global Apolitical Academy, a project to spur young people’s political and democratic engagements as well as F1RST which works with educational institutions and business on inclusivity and offers long-term support to young talent.

The first time I met Daniel many years ago, he told me that “When I was your age, I knew everything. Now, I’m certain of very little.” He said it with a big smile and with great warmth. Unknowingness does not disturb a person open to learn. At a much later instance, I asked Daniel from where this curiosity stems and without hesitation he responded: “from my mother”.

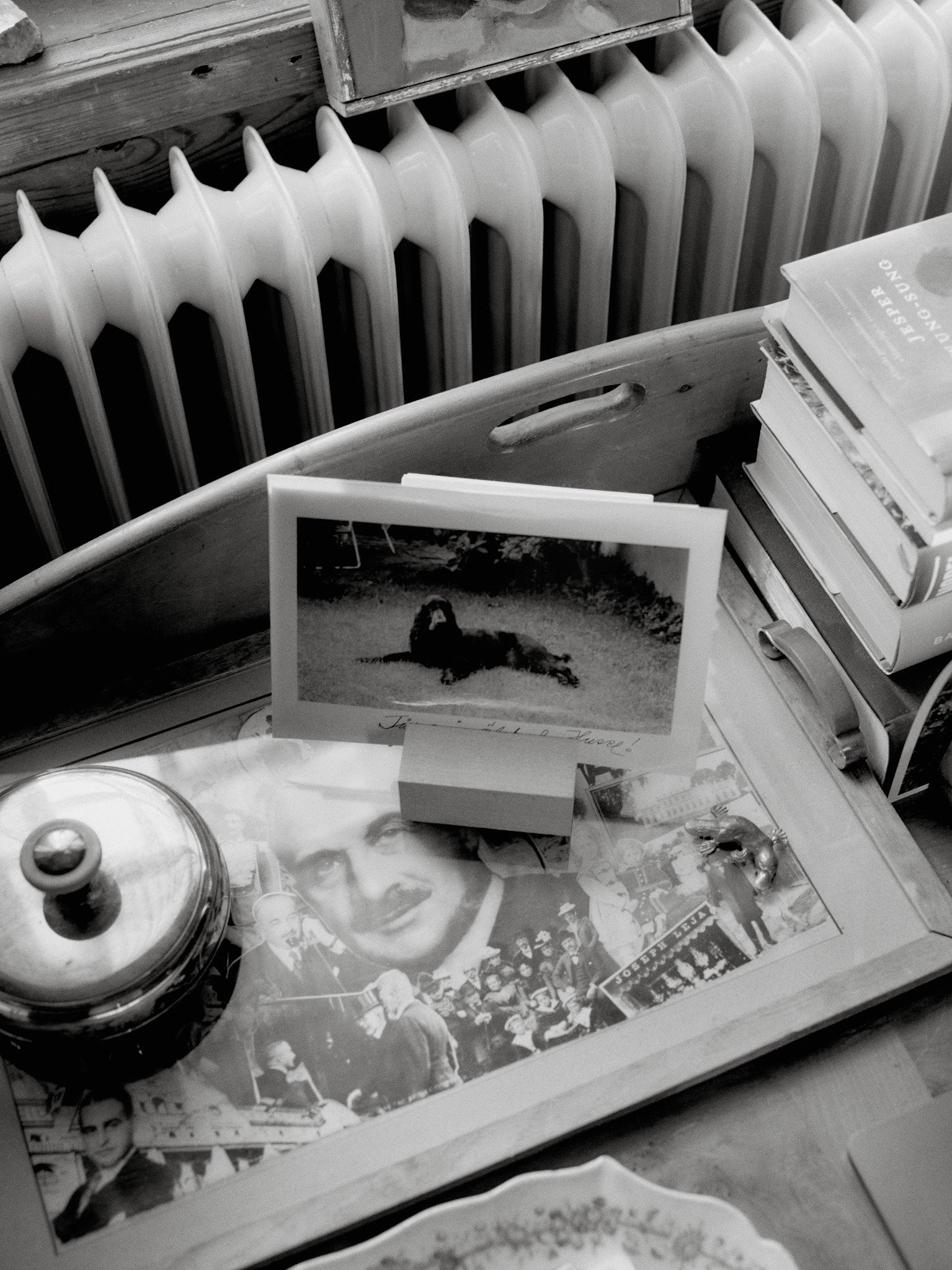

Information travels fast, however, wisdom builds over generations. In the comfort of Lisbeth Sachs’ home, we listen in on a conversation held between a mother and a son on social engagement, creativity and openness.

/Dag Granath

Stockholm, October 18th 2024.

DS: Shall we start?

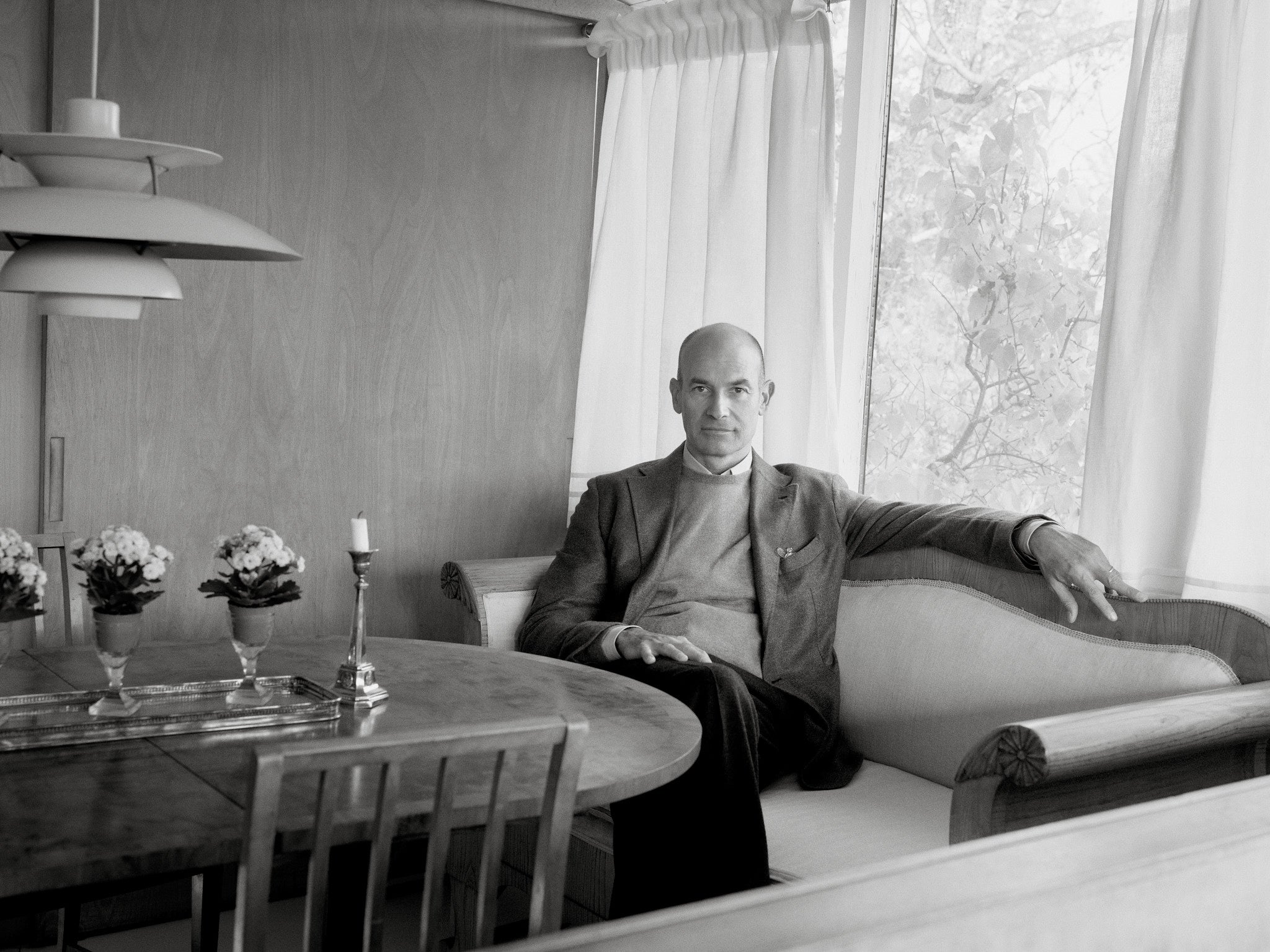

LS: I have thought a lot recently - as I’ve been sitting here in this room – about you growing up here and this room in particular. The room opens up to the outside world. You can see the boats passing by outside and I assume you must have felt that the outside world has been present in this room? Do you have any memories of your childhood and this room?

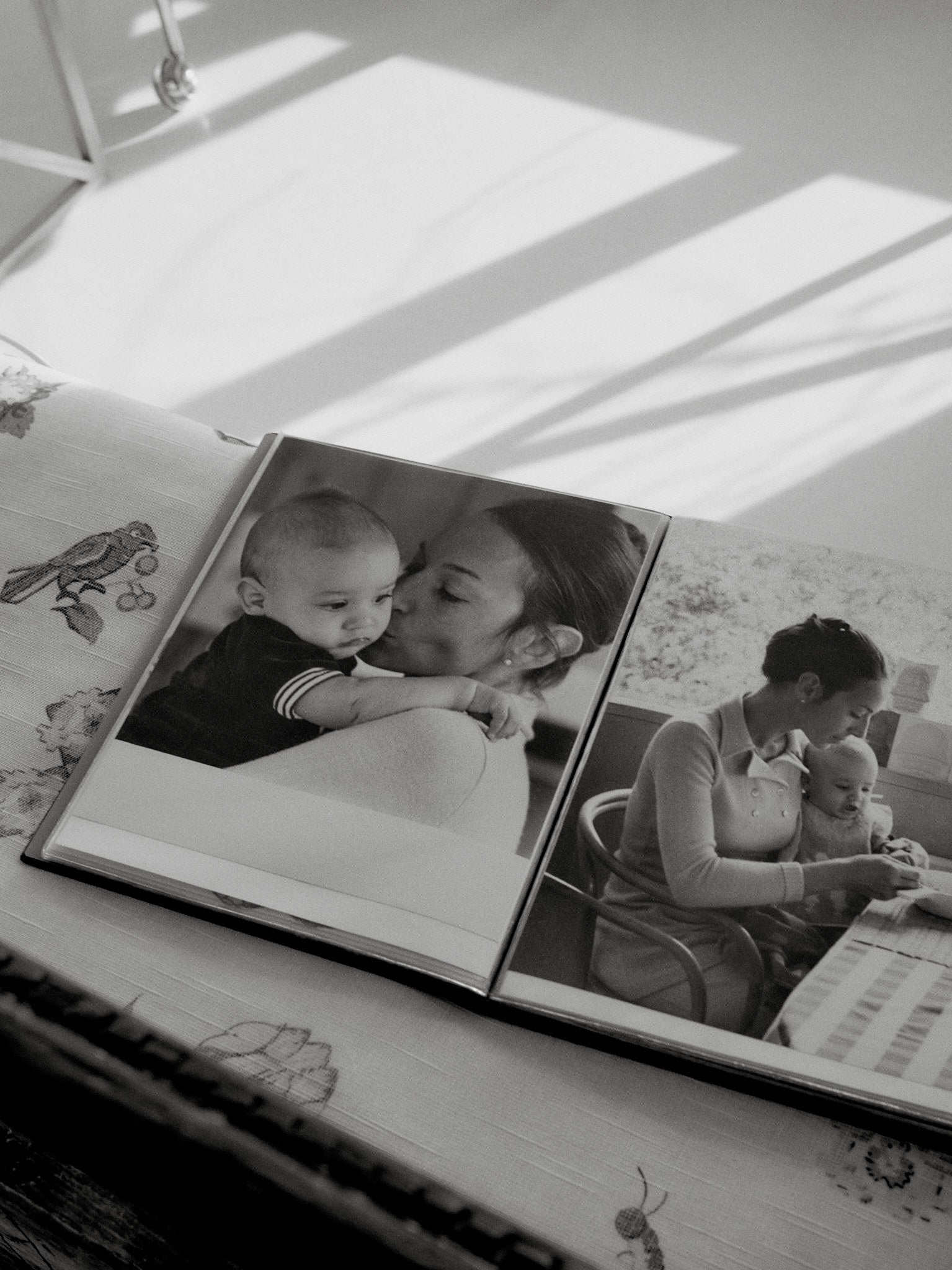

DS: Childhood memories are always difficult. What are my actual memories and what are the images I’ve seen depicting it? Still, I have to admit this room is the strongest visual memory I have of my upbringing.

LS: I am thinking about your curiosity – something you had already as a child. Growing up in an open space with the world ongoing must have sparked something.

DS: I am sure it did to some extent. However, I think the openness that you and my father brought to the dinner table had a much stronger impact on me.

LS: Yes, during those years I did my anthropological field studies. I was in Anatolia and Sri Lanka but also in the Swedish suburbs and I recall how active and engaged you were in that. What are your memories from that?

DS: I think that my engagement in society – for democracy and inclusion – later on in life was definitely inspired by and rooted in this early experience of meeting people with completely different backgrounds. You brought people here to the house that had grown up in different places and under different circumstances than myself. I think meeting people of different beliefs gave me a much broader palette. Being open – quite literally in this case with you opening up our house and your family.

LS: I’m thinking about your societal engagement. You are a globetrotter and a force in the world. I feel you have a very special approach to people and how you want to help. Can you describe that?

DS: Well, as I mentioned I think concepts of social justice and cohesion and the importance of social engagement was something I understood early on sitting around our dinner table. At the time, I probably thought it was quite vague and I was longing for something more concrete. Something practical to do. Later on in life when I went on to higher studies and thereafter, I have come to realize the privilege of my context and I became increasingly interested in working concretely to create an infrastructure of support for people who do not have that privilege. Reaching these young people need to start early. At F1RST [a project within Daniel Sachs Foundation] for instance, we are working with these children already from the age of 12-13 and follow them through elementary and high school and then onwards to higher education and their first job. It is a long-term engagement

LS: So young!

DS: Yes, at that age your dreams and fantasies about your future is taking shape. How can you dream about something you do not know exist and even less so have a clear idea about how to reach? Together with the leadership of selected high schools we reach these children and take them out to workplaces to show the opportunities that exist. We also include higher education institutions as well as companies in the community. We normally say that our work stops when these young talents get their first job. From there and onwards they will build their own network and community. We have almost 1400 young talents in the community already.

LS: It is a big commitment to provide substantial support to all these people. Engaging in young people without natural support from home is linked to our common future. I know from being close to such kids during my field studies how difficult it can be to even dream about fully participating in society. Many may end up in service professions which are much needed, but thanks to F1RST some of the talents which are invisible can be become visible and find their way to other dreams.

DS: Yes, but the value is always co-created and spread across larger groups. For instance, in our mentor program for young adults in higher education we offer them the opportunity to get a mentor who might have a job that they strive to get after their education. However, in order to get that mentor, they in turn will have to become a mentor for another younger person who is still in high school. This way, knowledge and network spreads across different generations in an organic way. We do not always have to be the provider, but we build the platform and the program that encourages people to share. Talent is everywhere and we just need to get talent the opportunity to grow.

LS: I also wanted to talk about art. You have told me that you do not like being guided through exhibitions of art. I feel something very similar. I want to experience art in a natural way and I don’t want to be told what the art is about.

DS: Yes, I prefer at least my first encounter with art to be unfiltered.

LS: On the other hand, this one time when we were picking mushrooms with Ulf Linde [Swedish art critic and member of the Royal Academy] he found a small piece of porcelain buried in the ground. I can’t recall the details, but he was talking about this piece of porcelain for over half an hour to my great enthusiasm. Maybe it was the fact that this “art experience” was so sudden and random so I was open to his story. I don’t know.

DS: There are different ways of experiencing art and to me art is something spiritual. I want to get struck emotionally when I experience art. It is also an escape from the intellect or shall I say a space where I want to allow my brain to rest and let my emotions and instincts to take over. One is constantly trying to understand things; analyze and figure things out. This is, I think, why I always look for an experience of art that just hits me in the gut. I think this is why I have always been drawn to dance. In dance, there is to me very little emphasis on “understanding”. It moves you or it doesn’t.

LS: So aren’t you curious where it all comes from?

DS: Of course, but that comes later. Once the art has had the space to move me I am happy to learn and can talk about it for hours, but I want to listen to my own reaction first. And to me, the understanding starts with the artist. I have had the privilege of meeting many artists and being able to talk to them about their work. Wanting to understand art is a very natural response. It’s a very human thing. But I have no longing to understand art, only to get struck by it.

LS: But you also buy art. With the art that you buy for yourself, are these pieces that have struck you in that way?

DS: Yes. Interestingly enough, I almost exclusively buy works on paper. I’m quite sure the reason why works on paper resonate with me is because works on paper were very present in our home when I was growing up. With dad being an architect, there were always sketches and drawings laying around, also drawings from friends of yours. There is something about the directness from hand to paper and the acceptance of imperfection, of the tentative formation of an early though or idea, that gets to me emotionally.

DS: What about dancing?

LS: Yes, I did dance ballet for many years growing up.

DS: Do you regret not doing it longer?

LS: Well, there is such joy and such comfort in dancing. It really is a beautiful thing. To share that experience with your fellow dancers.

DS: And your mother, who was a pianist, played for ballet students.

LS: Yes. Growing up with music is truly special. Your daughter in turn has also been smitten by the power of music so it seems to be a generational thing. When I listen to the radio and hear something that my mother used to play I can feel the music in my entire body.

DS: And that memory of music is not an intellectual memory but a bodily one.